Greater Kudu

Tragelaphus strepsiceros

General Description

Scientific Name: Tragelaphus strepsiceros

Subspecies: 3 subspecies

-

Cape Greater Kudu (T. s. strepsiceros)

-

Chora Greater Kudu (T. s. chora)

-

Western Greater Kudu (T. s. cottoni)

Status: Least Concern (stable)

Population Estimate: 300,000- 350,000

Population in Assessed Areas: 730

Diet: Herbivore - browser & grazer.

Male Size: 190-315 Kgs

Female Size: 120-210 Kgs

Trophy Size: 120 cm minimum (SCI)

Generation Length: 6.2 years

Reproductive Season: February to March

Time of Activity: Diurnal

Description: Greater kudus have a narrow body with long legs, and their coats can range from brown/bluish grey to reddish brown. They possess between 4 and 12 vertical white stripes along their torso. The head tends to be darker in colour than the rest of the body, and exhibits a small white chevron which runs between the eyes. Greater kudu bulls tend to be much larger than the cows, and vocalize much more, utilizing low grunts, clucks, humming, and gasping. The bulls also have beards running along their throats, and large horns with two and a half twists, which, were they to be straightened, would reach an average length of 120 cm (47 in), with the record being 187.64 cm (73.87 in). They diverge slightly as they slant back from the head. The horns do not begin to grow until the bull is between the ages of 6–12 months. The horns form the first spiral rotation at around 2 years of age, and not reaching the full two and a half rotations until they are 6 years old; occasionally they may even have 3 full turns.

The greater kudu is one of the largest species of antelope, being slightly smaller than the bongo. Bulls weigh 190–270 kg (420–600 lb), with a maximum of 315 kg (694 lb), and stand up to 160 cm (63 in) tall at the shoulder. The ears of the greater kudu are large and round. Cows weigh 120–210 kg (260–460 lb) and stand as little as 100 cm (39 in) tall at the shoulder; they are hornless, without a beard or nose markings. The head-and-body length is 185–245 cm (6.07–8.04 ft), to which the tail may add a further 30–55 cm (12–22 in).

Ecology: The greater Kudu's habitat includes mixed scrub woodlands (the greater kudu is one of the few largest mammals that prefer living in settled areas – including the scrub woodland and bush on abandoned fields and degraded pastures, mopane bush and acacia in lowlands, hills and mountains). They occasionally venture onto plains if there is a large abundance of bushes, but normally avoid such open areas to avoid their predators. Their diet consists of leaves, grass, shoots and occasionally tubers, roots and fruit (they are especially fond of oranges and tangerines).

During the day, greater kudus normally cease to be active and instead seek cover under woodland, especially during hot days. They feed and drink in the early morning and late afternoon, acquiring water from waterholes or roots and bulbs that have a high water content. Although they tend to stay in one area, the greater kudu may search over a large distance for water in times of drought, in southern Namibia where water is relatively scarce they have been known to cover extensive distances in very short periods of time. Since they are water dependent, they are at risk of being extirpated in parts of Southern Namibia, where aridification is eliminating the water sources they rely on.

Behavior: Greater kudus have a lifespan of 7 to 8 years in the wild, and up to 23 years in captivity. They may be active throughout the 24-hour day. Herds disperse during the rainy season when food is plentiful. During the dry season, there are only a few concentrated areas of food so the herds will congregate. Greater kudu are not territorial; they have home areas instead. Maternal herds have home ranges of approximately 4 square kilometers and these home ranges can overlap with other maternal herds. Home ranges of adult males are about 11 square kilometers and generally encompass the ranges of two or three female groups. Females usually form small groups of 6–10 with their offspring, but sometimes they can form a herd up to 20 individuals. Male kudus form small bachelor groups, but are commonly found as solitary and widely dispersed individuals. Solitary males will join the female herds only during the mating season (April–May in South Africa).

The male kudus are not always physically aggressive with each other, but sparring can sometimes occur between males, especially when both are of similar size and stature. The male kudus exhibit this sparring behavior by interlocking horns and shoving one another. Dominance is established until one male exhibits the lateral display.[13] In rare circumstances, sparring can result in both males being unable to free themselves from the other's horns, which can then result in the death of both animals.

Rarely will a herd reach a size of forty individuals, partly because of the selective nature of their diet which would make foraging for food difficult in large groups. A herd's area can encompass 800 to 1,500 acres (3.2 to 6.1 km2), and spend an average of 54% of the day foraging for food

Predation Predators generally consist of lions, spotted hyenas, and African wild dogs. Although cheetahs and leopards also prey on greater kudus, they usually target cows and calves rather than fully grown bulls. There are several instances reported where Nile crocodiles have preyed on greater kudus. When a herd is threatened by predators, an adult (usually a female) will issue a bark to alert the rest of the herd. Despite being very nimble over rocky hillsides and mountains, the greater kudu is not fast enough (nor does it have enough endurance) to escape its main predators over open terrain, so it tends to rely on leaping over shrubs and small trees to shake off pursuers. Greater kudus have excellent hearing and acute eyesight, which helps to alert them to approaching predators.[3] Their colouring and markings protect kudus by camouflaging them. If alarmed, they usually stand still, making them very difficult to spot

Reproduction Greater kudus reach sexual maturity between 1 and 3 years of age. The mating season occurs at the end of the rainy season, which can fluctuate slightly according to the region and climate. Before mating, there is a courtship ritual which consists of the male standing in front of the female and often engaging in a neck wrestle. The male then trails the female while issuing a low pitched call until the female allows him to copulate with her. Gestation takes around 240 days (or eight months).[2] Calving generally starts between February and March (late austral summer), when the grass tends to be at its highest.

Greater kudus tend to bear one calf, although occasionally there may be two. The pregnant female kudu will leave her group to give birth; once she gives birth, the newborn is hidden in vegetation for about 4 to 5 weeks (to avoid predation).[12] After 4 or 5 weeks, the offspring will accompany its mother for short periods of time; then by 3 to 4 months of age, it will accompany her at all times. By the time it is 6 months old, it is quite independent of its mother. The majority of births occur during the wet season (January to March). In terms of maturity, female greater kudus reach sexual maturity at 15–21 months. Males reach maturity at 21–24 months.

Conservation Analysis

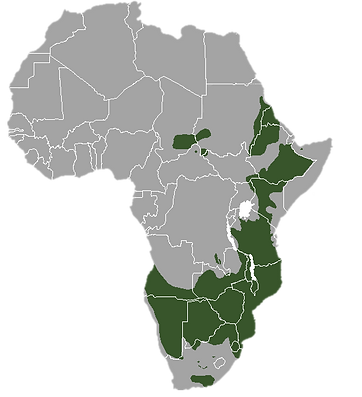

Current & Historic range: Historically, the Greater Kudu occurred over much of eastern and southern Africa, from Chad nearly to the Red Sea, south to the Eastern Cape, west to Namibia and north to mid-Angola. While it has disappeared from substantial areas, mainly in the north, it generally persists in a greater part of its former range than other large antelope species, as a result of its secretiveness and its ability to survive in settled areas with sufficient cover. Additionally, it usually doesn't compete with livestock, hence is tolerated over a larger range. As in the past, it is much more sparsely distributed and less numerous in the northern parts of its range (from northern Tanzania northwards) than further south.

In Eritrea Greater Kudu were observed in Semenawi Bahari on the escarpment north of Asmara in 2014 (Mallon 2014). The species may now be extinct in Djibouti, where a few were reported to survive in the south on the Ethiopia border in the 1980s (East 1999, Heckel and Rayaleh 2008). In Somalia, Simonetta (1988) suggested they may survive on the northern slopes of the Ga'an Libah in the north-west, where tracks and local reports were recorded by Mallon and Jama (2015); there are recently discovered museum specimens collected in the 1960s from south and central Somalia that expand the known historical range (Gippoliti and Fagotto 2012). There is no recent information on their status in South Sudan (they were not recorded during recent surveys in the south, Fay et al. 2007) or Uganda (East 1999).

Current & Historic Populations: Citing various authors, East (1999) indicates that population estimates are available for many parts of the Greater Kudu’s range, but many of these are based on aerial counts which tend to substantially underestimate this species’ actual numbers. The sum of the available estimates (352,000) is therefore likely to be considerably less than the true total numbers of the species. Population densities estimated from aerial surveys are frequently less than 0.1/km², even in areas where this species is known to be at least reasonably common. Higher densities of 0.2-0.4/km² have been estimated by aerial surveys in some other areas. Ground counts in areas where the Greater Kudu is common have produced population density estimates from 0.3/m² to 4.1/km² (East 1999).

East (1999) estimated a total population of around 482,000 Greater Kudu, with the largest populations found in Namibia, where the species remains widely abundant on private farmland, and South Africa. Population trends are generally stable or increasing on private land and in protected areas in southern and south-central Africa and Tanzania, but show a tendency to decline in other regions.

Threats to Species Survival: The Greater Kudu’s status is less satisfactory in the northern parts of its range, due to over-hunting and habitat loss. Greater Kudus are heavily hunted, however, this does not seem to be affecting the species' overall long-term survival as they seem to be quite resilient to hunting pressure and remain abundant and well managed in other parts of its range.

Recommended Conservation Actions:

-

Further resource and manage protected areas where Greater Kudu exist.

-

Encourage the implementation of economic incentives that allow landowners to profit off the presence of healthy sable population, whether that be through hunting or ecotourism.

-

Focus funds on recovering Kudu populations in the northern end of their historical range, were their populations are under the most threat.

-

Improve survey methods to get accurate population data, such as implementing long-term monitoring programs.

Country | Population Estimate | Population Status | Last Assessed |

|---|---|---|---|

Zimbabwe | |||

Zambia | |||

Uganda | |||

Tanzania | |||

South Sudan | |||

Rwanda | |||

Nigeria | |||

Mozambique | |||

Malawi | |||

Kenya | |||

Gabon | |||

Equatorial Guinea | |||

Democratic Republic of Congo | |||

Central African Republic | |||

Cameroon | |||

Angola | |||

South Africa |

*Further data on Greater Kudu populations and harvest numbers outside of South Africa and Namibia are largely incomplete, and hence it has not been evaluated by us. It is our goal to expand into other African Nations soon, so please do be patient with us.

Economic & Cultral Analysis

Ecotourism Value: High

Hunting Value: Very High

Meat Value: High

Average Trophy Value: $1,200 - 3,500 USD

Meat Yield per Animal: 50-140 kg

Economic Value/Impacts: In some regions, particularly rural area, Greater kudu and other wildlife species serve as a source of protein and sustenance for local communities. Greater are somewhat valuable to the ecotourism industry, being an animal that many visitors aim to see on their trip, due to being every well known by western visitors. They can be difficult to see at times, due to their shy nature, and habitat preferences.

The Greater Kudu is much sought after by hunters, both for the magnificent horns of bulls and more generally for their high-quality meat (Owen-Smith 2013). They are one of the most commonly hunted species in southern Africa, and generate the highest proportion (13.2%) of hunting income in South Africa (Patterson and Khosha 2005). Greater Kudu are also a favored game-ranching species, because as browsers they do not compete with domestic livestock (Owen-Smith 2013). The percentage of animals in offtake from ranching versus wild is not known, though is something that Faunus Wildlife Management intends to investigate.

Cultural Value: Greater Kudu have been pursued as prey by hunter gatherer tribes thousands of years, being a staple food source for communities in many areas. Local hunters often describe the species as the "grey ghost" due to their ability to seemingly disappear into the landscape once alerted, much to the hunters dismay. The meat, like most spiral horned antelopes, is incredibly delicious, and greatly valued by locals.

Region | Males Harvested | Females Harvested | Harvest Change | % of Population | Total Springbok Harvested 2024 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Namibia (Incomplete) | |||||

Limpopo | |||||

Mpamalanga | |||||

KwaZulu Natal | |||||

North-West | |||||

Free State | |||||

Eastern Cape | |||||

Northern Cape | |||||

Western Cape | |||||

All of South Africa |

*Much of the data on Greater Kudu harvest numbers across their range is largely incomplete, and hence it has not been evaluated by us. It is our goal to expand our data set as much as possible, so every data contribution is highly valuable to us.

![Faunus_1.0-_(no_background)[1].png](https://static.wixstatic.com/media/684ede_9119f109be044e24997ff22fdfd55e34~mv2.png/v1/crop/x_31,y_0,w_365,h_402/fill/w_87,h_96,al_c,q_85,usm_0.66_1.00_0.01,enc_auto/Faunus_1_0-_(no_background)%5B1%5D.png)

.jpeg)